Keywords: ● Strategy Implementation ● Family Business ● Small Business ● Succession ● Diversification ● Colli Bolognesi, Northern Italy

CASE SYNOPSIS

Alessandro and Alessandra Galletti were the owners of a small family-owned and operated vineyard in Northern Italy. They had owned Podere Riosto for 20 years and had grown the business to €1million in annual sales. Their flagship product, Podere Riosto’s Pignoletto, was a highly regarded and award-winning wine. Recently, however, Alessandro faced challenges relating to both business and family. He was unsure whether to invest in his wine business or follow a new opportunity in tourism; he was also considering expanding sales on a more global scale but knew there were many risks involved; and he was confronted with succession problems as his son was not engaged in the business and his daughter wanted to manage it all.

This case provides students with the external and internal challenges faced by a small family-owned business competing during times of economic uncertainty and family strife. After a short background on trends in the global and Italian wine market, as well as a history of Podere Riosto, the case presents the challenges faced by Alessandro. These challenges are divided into business issues and, separately, those relating to the family. Students are asked to attend to the business challenges first, and subsequently those relating to the family dynamics. Finally, the case allows students to reflect on the business and family spheres simultaneously in an effort to understand the interwoven nature of management and decision-making in a family-owned enterprise.

Alessandro Galletti, owner of wine producer Podere Riosto, and his wife Alessandra stood in their vineyard overlooking the hills of Bologna, in northern Italy. The warming day temperatures over the past few weeks hinted that spring was just around the corner. The buds on the vines would soon break, commencing a new growing season in 2012. The previous year had been a winner for Podere Riosto, both figuratively and literally. While erratic for Italy as a whole, the 2011 growing season for the Emilia-Romagna region delivered an abnormally dry period, mixed with episodes of moderate rains, resulting in perfect conditions for the region’s white wines. Podere Riosto’s flagship product, Pignoletto, was shaping up to be an excellent vintage year. Moreover, Alessandro was in advanced negotiations with a U.S. importer looking to introduce this lesser-known varietal to American palates. And to top it all off, Podere Riosto had been awarded the coveted Vitiviniculture Merit Medal at Vinitaly 2012, the largest annual fair dedicated to showcasing Italy’s vast selection of wines. To Alessandro and Alessandra, it seemed that Podere Riosto had reached another important milestone in its 20-year history. Yet Alessandro knew they could not rest on their laurels as new challenges arose.

In the fall of 2011, Italy’s economy had fallen into a tailspin due to the financial crisis playing out across the European Union. Straining under excessive debt levels and a political crisis stemming from the resignation of its prime minister, Silvio Berlusconi, Italy was poised to enter its second recession over a three-year period.1

Alessandro expected a spending slowdown, if not a downshift to lower priced wines, in 2012. Another issue on Alessandro’s mind concerned the imminent rollout of a new business opportunity at Podere Riosto. For the past five years, Alessandro’s and Alessandra’s daughter, Cristiana, had been championing the winery’s “agriturismo” project — in an effort to turn Podere Riosto into a farm-holiday destination. With a basic infrastructure in place and a marketing communications program ready to launch, Podere Riosto was ready to open its doors to tourists. But Alessandro wondered if the timing was right: would agritourism divert attention and resources away from the winery? Or was now the time to push forward and establish a toehold in this industry with historically strong growth prospects? Lastly, Alessandro and Alessandra, both in their 70s, had been having more frequent discussions about leadership and succession. Were they prepared to hand over the reins of the business to their daughter Cristiana?

ITALY AND THE GLOBAL WINE INDUSTRY

Wine had been central to the evolution of Western civilization since the beverage was first produced about 8,000 years ago. Wine production and consumption were said to have originated in what is today Iran, although widespread evidence exists among other early societies. Egyptians were known to bury their pharaohs with ample wine stocks to be savored on the journey through the afterlife. Greek and Roman enjoyment of wine gave rise to Dionysus and Bacchus, respectively, gods to be worshipped and thanked for the grape harvest. As organized religion began to consolidate and spread, wine remained part of important rituals, including the Eucharist in Catholicism and the chanting of the Kiddush – or blessings – for the Jewish Shabbat. Over the centuries, continuous innovation by vintners steadily improved the quality and added to an ever-growing assortment of wines.2

In more modern times wine was classified by its vinification method that is, by how it was made.3 These classifications included table, sparkling, and fortified wines. Table wines ranged in alcohol by volume (ABV) from 8.5 percent to 14 percent and comprised the overwhelming majority of global sales. Sparkling wines included carbonated wines from France’s Champagne, Spain’s Cava, and Italy’s Prosecco regions, as well as wines from regions without official territory designations. The last category, fortified wines, included Ports and Sherries, among others, that exceeded 15 percent ABV levels and tended to be sweeter and often consumed after a meal.

Italian table wines were universally renowned for their quality, consistency and innovation. The country’s twenty-two regions spanning the entirety of the geographic “boot” produced such notable wines as Tuscany’s Chianti and Brunello, Piedmont’s Barolo and Barbaresco, and Friuli- Venezia Giulia’s Pinot Grigio. Italy’s Ministry of Agriculture enforced four levels of quality assurance for Italian winemakers for the purpose of classifying and authenticating where and how wines were made. These four levels were as follows:4

- DOCG (Denominazione di Origine Controllata e Garantita): Wines receiving controlled and guaranteed designations of origin (DOCG) were considered to have passed the strictest regulations of production governing types of grapes, yield limits, geographic regions, alcohol content, and the length of aging. Wines with DOCG designations were marked with numbered government seals across the neck of the bottle. Approximately 70 Italian wines were classified as DOCG, with each wine comprising multiple producers. Wines assigned DOCG status often commanded the highest prices.

- DOC (Denominazione di Origine Controllata): Wines carrying DOC designations were also produced within narrow albeit more relaxed guidelines than DOCG wines. DOC-designated wines were much more prevalent throughout Italy, numbering in the hundreds.

- IGT (Indicazione Geografica Tipica): A fairly recent classification, IGT, introduced in 1992, indicated wines whose method of production fell outside DOCG and DOC guidelines. While IGT wines were often high quality, the designation provided wine makers a greater degree of freedom to experiment with production.

- VdT (Vino di Tavola): VdT was the least restrictive designation used to indicate table wines. Wines of VdT classification were often of lower quality and, accordingly, lower prices.

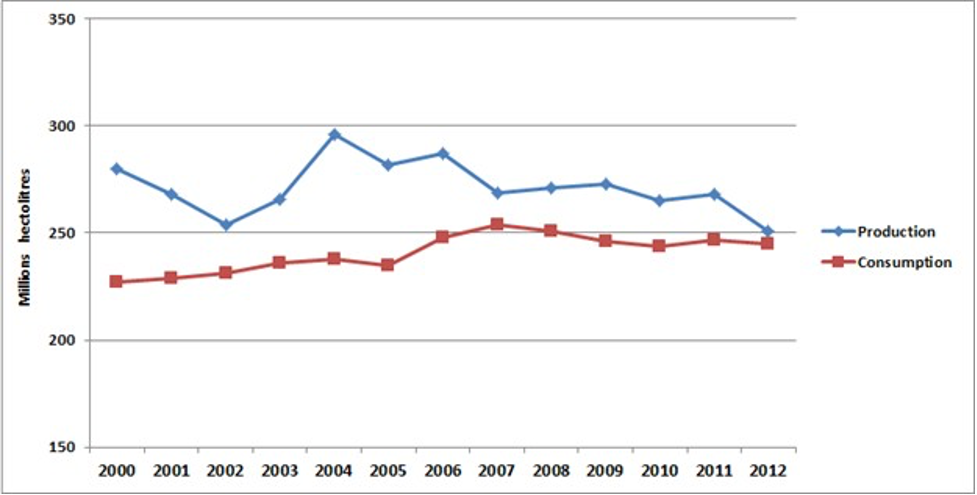

Over a five-year period beginning in 2007, global production of wine had stalled and slightly decreased from 266 million hectoliters (hl) to 252 million hectoliters (hl) in 2012 (see Exhibit 1). Europe continued to account for two-thirds of global wine production, with France taking the lead at 41 million hl, and Italy in second place, with 40 million hl. Global wine consumption mirrored the trend over the same five-year time span 2007-2012, decreasing from 251 million hectoliters to 243 million hl, an almost 5 percent drop. This decline was driven in large part by a reduction in per-capita consumption in wine-producing countries where consumers opted for quality over quantity, shifting their purchases away from bulk wines toward premium wines.

Exhibit 1. Global Wine Production and Consumption, 2000-2012

Italy’s wineries had been negatively impacted over that time, with production rates dropping 10 percent. Much of the decrease was attributed to increased competition from New World producers in Australia, Chile, Argentina, South Africa and New Zealand competing for the export market. Additionally, in the four years leading up to the recession, global supply had been outstripping demand, in turn drawing lower tiers of Italian wines into fierce price wars. While the wine market seemed to be stabilizing and even on the verge of recovery, by 2012 the unraveling political situation, coupled with Italy’s mounting debt crisis, looked to be dragging the country into yet another recession.

PODERE RIOSTO: HISTORY AND EVOLUTION

The 160-acre Podere Riosto winery was located just south of the city of Bologna. Producing red and white table wines, as well as a few sparkling wines, Podere Riosto’s flagship product was Pignoletto, a white wine made from its namesake grape varietal. With few exceptions, wines originating from Emilia-Romagna were less known, and, thus, less consumed, than their counterparts in other wine-producing regions throughout Italy. Only over the past decade had Pignoletto made inroads across Western European markets and, more recently, a handful of U.S. importers had begun to express interest in introducing Pignoletto to the American consumer.

In 1954, Alessandra’s father, Gino Franceschini, bought a plot of land, leaving it largely uncultivated. Alessandra and Alessandro met in 1957 and married in 1966. Over the next two decades, Alessandro worked as an engineer in large Italian ceramics, leather and machining concerns while Alessandra tended to their two children, Cristiana and Lorenzo. In the 1980s, Alessandro struck out on his own by launching his consulting firm, LOCRI. In 1992, upon her father’s death, Alessandra inherited the property. That same year, Alessandro and Alessandra resolved to start Podere Riosto and began planting vines. Within a few years, the vines produced quality grapes, which Podere Riosto sold to distributors, who then resold to wine producers. Podere Riosto continued as a contract grower for the next five years, although Alessandro started experimenting with in-house production of Pignoletto. While the quality was at times variable, the prospects looked promising. Funding Podere Riosto with proceeds from LOCRI, Alessandro started spending more time on the vineyard. In 2000, Alessandro and Alessandra made significant infrastructure investments (e.g., chilling system for fermentation and final refermentation, temperature-controlled tanks, pumps, filtration systems, autoclaves for final refermentation, etc.) to prepare to scale the business. That year, they also hired a seasoned enologist to raise the consistency and quality of the wine and to direct and coordinate production, with Alessandra taking over the administrative duties of Podere Riosto.

Over the next decade, Podere Riosto grew, first slowly then quickly, reaching EUR 1 million in annual sales on production of 80,000 bottles in 2011. The present-day operation had capacity to double that amount to 160,000 bottles, permitting Alessandro to take advantage of eventually expanding sales on current products and introducing new products in the future. Approximately 55 percent of Podere Riosto’s sales were allocated to on-premise channels (e.g., restaurants, hotels), with the remainder sold to retail for off-premise consumption. Due to heavier discounting, off-premise sales delivered gross margins of 35 percent, versus an average margin of 40 percent generated in on-premise channels. Three types of Pignoletto – Superiore (still), Frizzante (lightly fizzy) and Spumante (sparkling) - accounted for slightly over half (55 percent) of the vineyard’s total sales. In addition to another four white wines, the remainder of sales comprised ten reds as well as two sparkling wines. Of Podere Riosto’s 19 wine products, fourteen were DOC, and three were IGT certified. Two of their wines did not carry any designation (see Appendix 1 for a list of Podere Riosto’s wines, retail prices and designations).

Family Involvement

In 2011, Cristiana and Lorenzo were, respectively, 44 and 41 years of age. During the early years of Podere Riosto, their involvement had been minimal since they dedicated most of their time to their schooling. Lorenzo married his college sweetheart and eventually joined her family’s woodworking business where he was responsible for international sales. While Lorenzo still occasionally advised Alessandro and Alessandra in matters concerning Podere Riosto, for the most part he sought to remain uninvolved. Lorenzo voiced his reason for not wanting to engage in his parents’ business: “I stepped back…there is no professionalization and the inclination toward conflict (in our family business) is very high.” 5

Cristiana, on the other hand, joined her father’s consulting business, LOCRI, upon graduating from college, where she worked with clients to expand their sales efforts. While expecting her first child in 2002, Cristiana, on a fluke, signed up for an agritourism class at a local continuing education center to learn more about the farm-holiday industry. Cristiana’s initial intention was to take only the first class. However, three years later, Cristiana eventually completed the entire course offering, including internships, and in the process obtained necessary certification to make Podere Riosto eligible to be a farm-holiday destination.

The Farm Holiday Opportunity

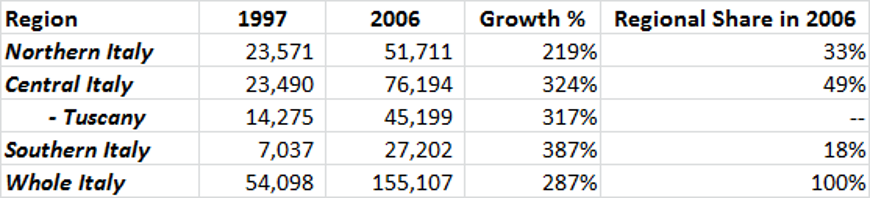

Agritourism made up only a very small percentage of worldwide tourism, although it had grown in popularity over the past three decades. By making their accommodation available to visitors, farmers initially sought to create ancillary revenue streams, especially during the off-season between harvesting and planting. More recently, many farmhouses derived an increasingly larger share of their income from their hospitality offerings. These offerings usually carried a healthier gross margin and, more importantly, net margins.6 Today’s farm holiday offerings ranged from basic lodging to deluxe facilities including on-premise restaurants, spas and workout facilities, and business centers. For guests, the appeal was primarily in the authentic experience offered by the farm holiday, which was often characteristic to the region, as well as the opportunity to enjoy the outdoors. As one of Europe’s leading destinations for farm holidays, Italy’s agritourism industry was experiencing exponential growth; over a ten-year period starting in 1998, the number of farm holiday options throughout Italy doubled (see Exhibit 2 and Exhibit 3) in an effort to keep up with demand.

Exhibit 2. Number of Stays and Number of Agritourism Farms in Italy, 1998-20077

Exhibit 3. Change in Number of Beds in Agritourisms by Region, 1997 – 20068

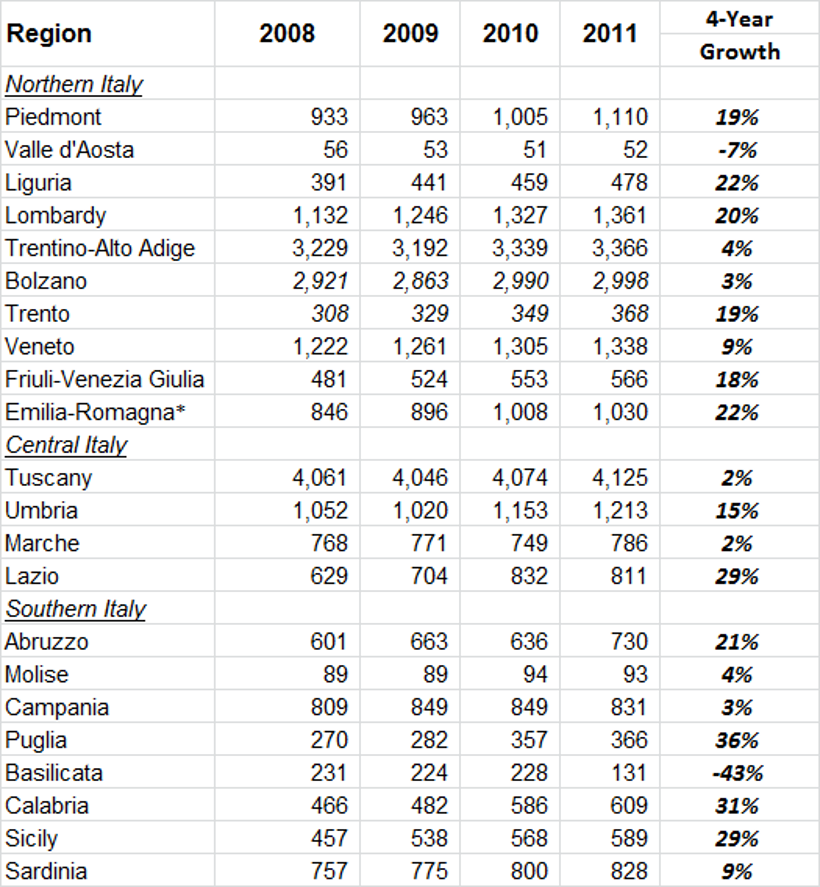

Of Italy’s twenty-two regions, Puglia, Calabria and Sicily, all located in the South, led the growth of agritoursim from the 2008 – 2011 time span (see Appendix 2). During the same period, Emilia- Romagna added over 180 farm holiday offerings, or approximately 22 percent. While Italian tourists frequented Italy’s farm-holiday destinations, most visitors came from abroad, including the United Kingdom, Germany, the Benelux countries (Belgium, Netherlands and Luxemburg), as well as Scandinavia countries.

With the necessary state certification in hand and intent on taking advantage of the burgeoning opportunity in agritourism, Cristiana, in 2006, set out to build Podere Riosto’s farm-holiday program. To begin, Cristiana invested in basic infrastructure by renovating an old farm house on the vineyard’s premises. This allowed Podere Riosto to host up to 23 guests in seven guest apartments. She also hired an architect to draw up plans for a space that would serve tastings and host events. Initial promotional efforts for Podere Riosto’s farm holiday were limited to Facebook, Tripadvisor and other social media in an effort to gauge interest.

In 2008, just as Cristiana was beginning to see the fruits of her labor, she was involved in a life- threatening car accident and was forced to withdraw temporarily from the project, while handing over the reins of the farm holiday business to her father. Alessandro said of those times: “It’s a miracle she’s alive…at the time, I told her ‘well, at this point, I’ll finish the things we had said we wanted to do.’ ” While the farm holiday offerings remained behind schedule due to Cristiana’s setback, by late 2011, Alessandro had completed Podere Riosto’s agritourism operation including the tasting room expansion that could double as a venue for special occasions such as weddings and corporate events. The double-occupancy rate was priced at EUR 120 per room during high season and EUR 80 per room in the off-season. Alessandro expected to generate a 60 percent gross margin on Podere Riosto’s accommodations and margins up to 50 percent on events hosted in its tasting room.

Issues around Decision-making and Succession

Responsibility for the different aspects of Podere Riosto was an ongoing source of conflict between Cristiana and her parents, causing many decisions to be made in exasperation. Alessandro was clear in terms of how decisions were made: “Both my wife and I have the last word, since we are the ones who control the day-to-day operation.” Cristiana, on the other hand, deemed her role and responsibilities within the family business to be on the same level as those of her parents:

My father is very experienced in production, my mother knows administration….I should be the sales expert. This would be logical but it isn’t so. Instead, my mom and dad make decisions and I follow up. But really, it’s a patriarchal leadership.

Alessandro and Cristiana quarreled over seemingly trivial issues. One recent argument concerned the design of a press release announcing Podere Riosto’s Merit award. After reviewing Cristiana’s first attempt, Alessandro, displeased with the results, took over the process. “Look, I stand for the company…I have a distinct aesthetic understanding. I had to rewrite it, but not because I wanted to.” Yet these squabbles hinted at deeper-seated differences of opinion over Podere Riosto’s strategic market positioning. For example, Alessandro firmly believed his wines warranted prices aimed at a higher end segment: “I’m making wine that gets a rating of 93 points…and I sell it only for EUR 9. This is laughable!” Cristiana, though, considered taking Podere Riosto’s pricing strategy in the opposite direction:

In my opinion, nowadays it’s more crucial to have more people and a slightly lower price rather than a competitive price and few people… I would rather have a higher volume and a lower price and profit per unit than lower volume and higher profitability.

The farm holiday’s strategic focus had been also part of this ongoing discord. With the project nearing completion, Alessandro was intent on realizing a return on the family’s investments. A year earlier, Cristiana had become reengaged with Podere Riosto after her health started to improve. However, the after effects of the accident, including fatigue, continued to impact her daily life causing her to work half-time or take off the occasional day. Having taken over the project from Cristiana during her recovery period, Alessandro had formed his own vision of Podere Riosto’s potential as a tourist destination:

I have an idea of what the farm holiday could become one day. Ours is a farm accommodation at a higher level, so I don’t need every Tom, Dick and Harry coming here. In this way, the agritourism also helps [position] the wine.

Cristiana, on the other hand, felt strongly that Podere Riosto should cater to a clientele seeking an affordable experience. By pricing on the lower end, Cristiana reasoned, the farm holiday would attract more visitors who subsequently helped spread the word. In time, prices could be readjusted upwards: “We will start low and, once this place is well advertised, we can grow step by step.” Alessandro took issue with this approach, expressing his concern: “We live in a world where people prefer paying more the first time rather than seeing prices increase over time.”

The topic of succession had yet to be openly discussed within the family. Cristiana conceded that she had “no idea” what her parents had in mind. However, she felt the leadership of Podere Riosto’s agritourism, in the meantime, should belong to her, especially given that she had been the one responsible for conceiving the farm-holiday opportunity. Cristiana believed her father should remain involved, but the ultimate decisions regarding the direction and day-to-day operation of the farm holiday should be made by her. Cristiana shared her sentiments with her father:

I would like to hear you say something along the lines of ‘take care of this project for the next three months, report back then’…and, eventually, ‘Cristiana, I am ready to step back and I will follow you…by your side, but a step behind. This way, Cristiana, you decide. What tires me out in this family job is the constant ‘Here’s what I think you should do…

Alessandro was deeply skeptical of Cristiana’s understanding of the farm-holiday business and the skills necessary to make it work: “There are things you don’t know that you should! In order to participate in the decision-making, it’s necessary to know things!” Cristiana shared her frustrations:

Unfortunately, I have a different vision, a different way of doing things… I would really like to be in a position where I can listen to my father’s suggestions and receive his guidance on administrative and operational issues, but in the end I’m the person responsible for the decision. Right now, when my father realizes he doesn’t get something his way, he says ‘fine, you do it. I don’t want any part in it.’ It’s not that we want to hurt each other, but we end up that way.

On occasion, and in private, Alessandro and Alessandra talked about the ownership of Podere Riosto being divided equally among Cristiana and Lorenzo. Yet when and how this transition would occur remained unclear. When prompted to provide a timeline for succession, Alessandro, laughing nervously, admitted, “We are not at all prepared. It will take forever!”

LOOKING AHEAD

With Italy’s economic outlook highly uncertain, Alessandro considered Podere Riosto’s future, especially in light of some of the opportunities that lay before him. One matter of concern involved pricing. Having been awarded the medal for his Pignoletto, Alessandro felt the timing was right to raise prices across all Podere Riosto’s wines. However, Alessandro also recognized the possible backlash from retailers and wholesalers that could follow the price hike, especially given the highly competitive domestic market. Furthermore, while wine, as a general category, was recession-resistant, Alessandro, nevertheless, worried Italian consumers, seeking to maintain their levels of wine consumption, would become increasingly price sensitive and switch to cheaper wines. Italian wine drinkers were already accustomed to enjoying quality wines priced below EUR 7 purchased at the local supermarket. Lastly, Alessandro felt any price increase in his wines needed to be accompanied by a price hike in the farm stay offering for the purpose of maintaining brand consistency.

Alessandro also considered the possibilities of geographic expansion, given that Podere Riosto’s infrastructure could support double its current production capacity. Sales outside Italy carried both risks and rewards. For one, retailers and wholesalers within the European Union gave preference to their home producers, thus widening the scope of competition. To break into these channels effectively, Podere Riosto needed to boost its marketing and sales efforts and to educate potential buyers on the distinctiveness of its wines. Additionally, wine consumption in northern EU countries (e.g., Belgium, Netherlands, Germany, Sweden, etc.) was significantly lower than in Mediterranean countries as beverage consumers in Northern Europe typically chose beer over wine9. Alessandro was especially intrigued by opportunities across the Atlantic Ocean. Over the past decade, the U.S. wine market had seen steady growth and now represented the third-largest market, in terms of consumption, behind France and Italy. By 2011, Americans consumed, on average, 2.7 gallons of wine annually, a 33 percent increase over the previous decade as they continued to embrace new wines (e.g., varietals, regions, etc.).10 While this level of consumption was much lower compared to Italian consumers (approximately 14 gallons of wine per person per year), American consumers, nevertheless, were willing to pay, on average, more for their wine purchases. Yet there were challenges to the U.S. market as well, where a distinct three-tier system separated the functions of producing, distributing and selling alcoholic beverages. Most states, with a few exceptions, prohibited the sale of wine directly from producer to retailer. This meant that wholesalers exerted strong influence over which wines made it to market.

Furthermore, the added step of distributing through wholesalers often increased the price of wine to the consumer. It was not uncommon for a bottle that costs USD 7 to produce to be sold by the wholesaler for USD10, to be subsequently priced at USD 15 in a store and USD 30 in a restaurant. For smaller producers of moderately priced wines (e.g., USD 15 at retail), gross margins averaged about 50 percent, with pretax profits in the single digits.11 With regard to imported wines, consumer tastes had also been shifting away from Old World wines towards those produced in New World countries. By 2012, Chile, Argentina and Australia wines constituted 75 percent of U.S. bulk wine imports. Lastly, a weak U.S. Dollar posed a challenge for European companies looking to export there. Alessandro recognized these obstacles to entering and gaining a footing in the American marketplace. However, Alessandro’s recent conversation with an importer in New York indicated there was strong interest in Podere Riosto’s award-winning Pignoletto.

Alessandro worried about how to proceed with the farm-holiday opportunity. The “soft” opening of the agritourism program had drawn, over the past six months, a handful of visitors. But Alessandro recognized that to secure a steady flow of tourists he needed to significantly increase promotional efforts. Two issues weighed on his mind. First, while farm holidays provided an attractive alternative to the price-conscious traveler, the unraveling economic situation in Italy and across Europe was bound to negatively impact tourism, in general, for the foreseeable future. Considering the financial outlays to date towards the farm stay, Alessandro was eager to begin harvesting his investment. Second, Alessandro feared that spending money to get a competitive foothold in agritourism could potentially undercut the wine business. Working with a limited marketing budget, Alessandro considered the trade-offs between growing an already established wine label versus nurturing the farm-holiday start-up to its full potential.

Management of Podere Riosto going forward remained unclear. Although, it was never openly discussed, the issue of succession troubled Alessandro, especially since he had recently celebrated his 71st birthday: “The future is something that my wife and I should have started thinking about way back.” Alessandro remained unsure about Cristiana’s leadership abilities:

It would be great to be able to tell Cristiana ‘from now on, the farm holidays is your responsibility.’ It would be awesome…but she has a limited understanding of the business. She doesn’t realize it is very demanding and one person alone cannot succeed.

A possible solution involved handing the business to both Cristiana and her brother Lorenzo, to be split evenly among them. But Lorenzo didn’t believe this arrangement to be feasible, given his own family’s needs: “It’s a question of profitability. We have two families to support and if you run the numbers, considering that we produce 80,000 bottles a year, we wouldn’t make enough money for both families.” As to his future involvement in Podere Riosto, Lorenzo was unsure: “I must say that I honestly don’t know what I will do in my life.” For the near term, Cristiana believed she was ready to be solely responsible for the sales and marketing aspects for both the wine business and the agritourism. Acknowledging her weaknesses in production and finance, Cristiana admitted: “I should spend time with Dad to be able to learn [wine making], since I need it, and next to Mom in order to learn the bookkeeping of the business.” It was becoming increasingly apparent to Cristiana that the current arrangement was not working out: “I cannot last much longer in this situation. It’s wearing me out.” Alessandra concurred with her husband’s assessment of the situation:

We’ve put so much time, effort and money into this vineyard…I try not to think about the future. I leave that to my husband. However, it causes him worry because he doesn’t see a clear path. He says to me ‘look at all the sacrifices we’ve made’…Lorenzo isn’t interested…and Cristiana would like to do a thousand things, but…

Walking through the vineyard, Alessandro contemplated the future of Podere Riosto: “We’ve accomplished something really important with this business, without making mistakes. To achieve the next level we need to think and act rationally. Otherwise we risk talking about everything and nothing.”

ENDNOTES

1 OECD (2012) OECD Employment Outlook, 2012: How Does Italy Compare? Retrieved from: http://www.oecd.org/italy/Italy_final_EN.pdf.

2 Lukacs, P. (2012). Inventing wine: A new history of one of the world’s most ancient pleasures. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company.

3 Nickles, J. (2015). 2015 Certified Specialist of Wine Study Guide. Washington, DC: Society of Wine Educators.

5 Galletti, Alessandro and Alessandra Galletti, Cristiana Galletti and Lorenzo Galletti. Personal interviews with Michael Braun, Pianoro, Italy, November 14, 2011.

6 Schilling, B. J., Attavanich, W., & Jin, Y. (2014). Does agritourism enhance farm profitability? Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics, 39(1): 69–87.

7 Ohe, Y. & Ciani, A. (2012). Accessing demand characteristics of agritourism in Italy. Tourism and Hospitality Management, 18(2): p. 284.

9 European Spirits Organization (2011). EU Alcohol Consumption Litres Per Capita, Adult Population. http://spirits.eu/files/58/table-consumption-per-capita.pdf

10 Wine Institute; http://www.wineinstitute.org; Economist, March 22, 2012.

11 Jordan, D., Aguilar, D., & Gilinsky, A. (2010). Benchmarking winery financial performance. Wine Business Monthly. Winebusiness.com. http://www.winebusiness.com/wbm/?go=getArticle&dataId=81514

Appendix 1: Podere Riosto Wine Products, Prices and Designations

|

White Table Wines

|

|

|

|---|---|---|

|

• Due Torri Bologna Bianco:

|

€8.50

|

(DOC)

|

|

• Pignoletto Frizzante:

|

€7.00

|

(DOC)

|

|

• Pignoletto Superiore:

|

€7.20

|

(DOC)

|

|

• Stilla:

|

€8.50

|

(IGT)

|

|

• Chardonnay:

|

€7.00

|

(DOC)

|

|

• Doraluce:

|

€8.50

|

(DOC)

|

|

Red Table Wines

|

|

|

|

* Aquilante:

|

€9.00

|

(IGT)

|

|

* Barbera:

|

€7.50

|

(DOC)

|

|

* Barbera Frizzante:

|

€7.00

|

(DOC)

|

|

* Cabernet Sauvignon:

|

€8.00

|

(DOC)

|

|

* Due Torri Bologna Rosso:

|

€8.50

|

(DOC)

|

|

* Gaudio:

|

€13.00

|

(IGT)

|

|

* Grifone:

|

€9.00

|

(DOC)

|

|

* Medoro:

|

€10.00

|

(DOC)

|

|

* Merlot:

|

€8.00

|

(DOC)

|

|

* Vecchio Riosto:

|

€8.00

|

(no designation)

|

|

Sparkling Wines

|

|

|

|

* Ludovico di Riosto Bologna Spumante:

|

€9.50

|

(DOC)

|

|

* Riosto Pignoletto Spumante:

|

€8.50

|

(DOC)

|

|

* Spumante Rosè For You:

|

€9.50

|

(no designation)

|

Source: Podere Riosto

Appendix 2: Certified Agritourism Operators by Region 2008-2011

Source: Istituto della Statistica Nazionale, 2014. Noi Italia: 100 statistiche per capire il Paese in cui viviamo, p. 177. Retrieved from http://www.istat.it/it/files/2014/03/Noi-Italia-2014.pdf.

*Podere Riosto is located in this region