Sandra K. Newton | Linda Nowak | Jialing Li

in press

Date accepted: June 15, 2020

Keywords: Differentiation strategy; tourism; wine tourism; entrepreneurship; opportunity analysis; franchising; franchise; France; champagne.

Case Summary

Nathalie Spielmann and Fabrice Parisot founded Prise de Mousse (PdM), the first and only champagne bar and shop in the Champagne region in France. Capitalizing on the popularity of the Champagne region as the second most visited in France, PdM had become a successful destination for both locals and tourists. The owners had recently been approached about possibly expanding their business through franchising.

Prise de Mousse’s unrivaled singularity plus its success and growth suggested to Nathalie and Fabrice that they could be on to something big. Considering their prior work commitments, financial obligations, and labor shortage challenges, the co-owners weighed their options. Where should Nathalie and Fabrice go from here? A question remained: to franchise or not to franchise?

The case includes information on the history and operation of the business, as well as background on the champagne tourism industry. PdM’s story, exhibits, and financial data provide sufficient evidence to evaluate its challenges, financial situation, market positioning, and opportunity analysis.

Prise de Mousse was not only a wine bar & store, but also a tourism operator for small champagne producers and growers. California wine tourism was a good example to compare with this case. Numbers of wineries located on the sides of Highway 29 in Napa Valley were open to the public daily. Direct to consumer sales were considered the key revenue of most wineries in California. There had been a shift in wine tourism from a focus on wine-production processing activities to an emphasis on authentic experiential values related to recreational activities, which was what PdM offered - "shepherding the discovery of the Mountain of Reims and its terroirs and to enable the best possible champagne experience."

Wine regions like Champagne, where producers and growers were located in separated locations; tourism operators were playing a vital link to help visitors have that authentic experience. With France having the lowest level of English speakers in Europe, bi-lingual (French and English) PdM employees were essential for the non-French visitor. The emerging wine business such as PdM showed optimistic potential for the development of champagne tourism.

The high labor costs and lack of skilled workers were major issues for many French businesses. With high labor costs and high unemployment, it was not likely that the French government would solve this issue in short time. Thus, for PdM they may consider the following recommendations:

Next steps to transform PdM to an entrepreneurial growth venture

Step 1: Keep an eye on talents who were willing to commit to the business.

Since both Nathalie and Fabrice had their full-time jobs and each of them dedicated extra hours to PdM. With the average 40 percent monthly sales growth rates, it was essential to have a responsible manager committed to the business. Although it was difficult to find qualified and loyal talents, any vacant position had to be filled as quickly as possible. Key elements for any position within PdM were professional knowledge, second language competence, and commitment to the job. Wine schools could have been possible resources to find qualified talents.

Step 2: Keep local producers/growers interested, and improve understanding of PdM’s business model as an outlet of developing brand equity and building memberships and winery customers.

The growth rate of partner memberships was stable. Since most French wine producers did not tend to work together, they did see PdM as a viable alternative to sell their products. However, not all of them truly understood the business model as an outlet of developing brand equity and increasing winery customers. Thus, it was possible that wine producers may drop out of the program if they did not see a significant increase in its bottle sales. Prise de Mousse had to keep those partners interested and engaged in the program, especially as the membership fee accounted for 17 percent of the revenue.

Step 3: Approach winemakers/growers in other villages to determine interest and build long-term strategic relationships.

As the business was still growing, gaining visibility and expecting higher profits for the second year, it was possible for the owners to consider growth options. Because the business model was built on a strong relationship between the owners and local producers, Nathalie and Fabrice had the need to expand and build long-term relationships within other villages’ winemakers and growers before they make any decisions to expand to other villages. This was one of the critical elements for this type business to achieve success.

Alternative approaches and their Pros and Cons

Recommendation #1: Stay the same and overcome labor shortagesThis alternative option is always one to consider and will be the “low-hanging fruit” option. |

|

|

Pros

|

Cons

|

|

+ Nothing has to change

+ Control of brand image and everything

+ Expecting high sales growth rate, profit is promising

+ Maintain and expand partnerships

+ Increasing value of the land in the Champagne Region

|

- Daily involvement of owners’ time into the business; possible burnout of owners at some point in time

- Hard to solve labor shortage issue

- Lack of cash flow to buy out the inventories

- Profit margin growth slow

- Partners may drop out of the program if they do not see a significant growth

|

Recommendation #2: Expand to other villages in Champagne regionThis would be the next viable option, because of the strong relationships between the owners and local producers. Owners would need to reach out and work to build strong relationships within other producers in other villages. |

|

|

Pros

|

Cons

|

|

+ Expansion capital acquisition

+ No risk of debt

+ No cost of equity

+ Growing brand image and awareness

+ Initial involvement of daily operation

+ Opportunity to develop another champagne concept (different style of champagne focus)

+Possible local investor help

|

- Risk of equity, unless investors found

- May require active involvement of daily operations

- No control for maintaining brand image (social media, customer feedbacks)

- Lack of qualified talent

- Less control over managers (hard to get everyone stay on the same page)

|

Alternative option: Consider Expanding through FranchisingThis option may come up if Entrepreneurship course. This option is not viable in the near-term as the owners have yet to pay themselves. What makes PdM a business to be franchised? Nathalie and Fabrice would have to determine whether they could meet any interested parties’ expectations as to the benefits of buying a PdM Franchise. Other questions that Nathalie and Fabrice might consider:

While Prise de Mousse should not consider franchising to increase its cash flow in the near-term, it could entertain the idea of franchising as a long-term plan. |

|

|

Pros

|

Cons

|

|

+ Expansion capital acquisition

+ No risk of debt

+ No cost of equity

+ Growing brand image and awareness

+ No involvement of franchisees’ daily operation

+ Globally promoting Champagne as a region and champagne as a product

|

- Extra efforts to main brand image (lack of qualified talent)

- Less control for maintaining brand image (social media, customer feedbacks)

- Less control over franchisee managers (hard to get everyone stay on the same page)

- Liability risk of unprofitable/uncooperative franchisees

- Logistic cost and potential storage problem

- Competitions with other sparkling wines

- Lack of authenticity (without the actual vineyards while tasting champagne)

- Loss of tourism operator function

|

Growing Wine Tourism in Champagne: Is a Champagne Bar Ready to Offer Franchises?

Download PDF of Full Research Article

It was a peaceful Sunday night in October 2018 in the village of Rilly-la-Montagne, located near the foothills of Montagne de Reims (Reims Mountain), Champagne, France. The lights from the Prise de Mousse (PdM) champagne bar and shop were still on, as Nathalie Spielmann and Fabrice Parisot, co-owners of PdM, were closing up for the night.

Nathalie said, “Fabrice can you help with the inventory for this quarter? I want to make sure we have the exact numbers when we give invoices to the winemakers.”

“Why don’t we just buy the wines, and then there won’t be any problems with our inventory,” Fabrice questioned.

“Well, that would work,” Nathalie said. “We were profitable our first year, but we’d need to come up with some strong cash flow if we bought their inventory.”

“Okay. Maybe we could increase our cash flow some other way. I received a phone call yesterday from a winemaker, who had visited us recently. He liked our champagne bar and shop concept and was asking if we are interested in creating another PdM in his village. I told him it sounds like an interesting idea, but we will have to look into it.” Fabrice smiled. “Would we want to offer franchises? Is franchising the way to grow our business? Either way, it sounds like a great way to get a return on our investment.”

“Well, I don’t think we’re there yet.” Nathalie continued, “I believe that most wine consumers know champagne as a product, but most of them do not know that there are specific regions that give a specific profile to the champagne. A foreign market could significantly help to promote the champagne region and PdM.”

“I understand where you’re coming from,” Fabrice said. “While there are many things we need to consider, let’s investigate our options in February when we are closed for vacation. Let’s just take it slowly; we don’t have to decide now. So, let’s get started on that inventory.”

Prise de Mousse had just been open a year, and its success had attracted the interest of tourists, both local and beyond. The Champagne region was expecting an increase of visitors from around the globe. Would there be a need for more businesses like PdM? What might be the next steps for PdM? Should Nathalie and Fabrice consider expanding PdM to other villages? What options do Nathalie and Fabrice consider? Where do Nathalie and Fabrice go from here?

INDUSTRY OVERVIEW

Wine tourism played a vital role in French tourism with France as one of the most popular tourist destinations in the world with 83 million international visitors in 2016.[i] Wine tourism has been defined as the visitation to vineyards, wineries, wine festivals, and wine shows. The primary motivating factors for visitors were wine tasting and experiencing the ambience of a grape wine region.[ii]

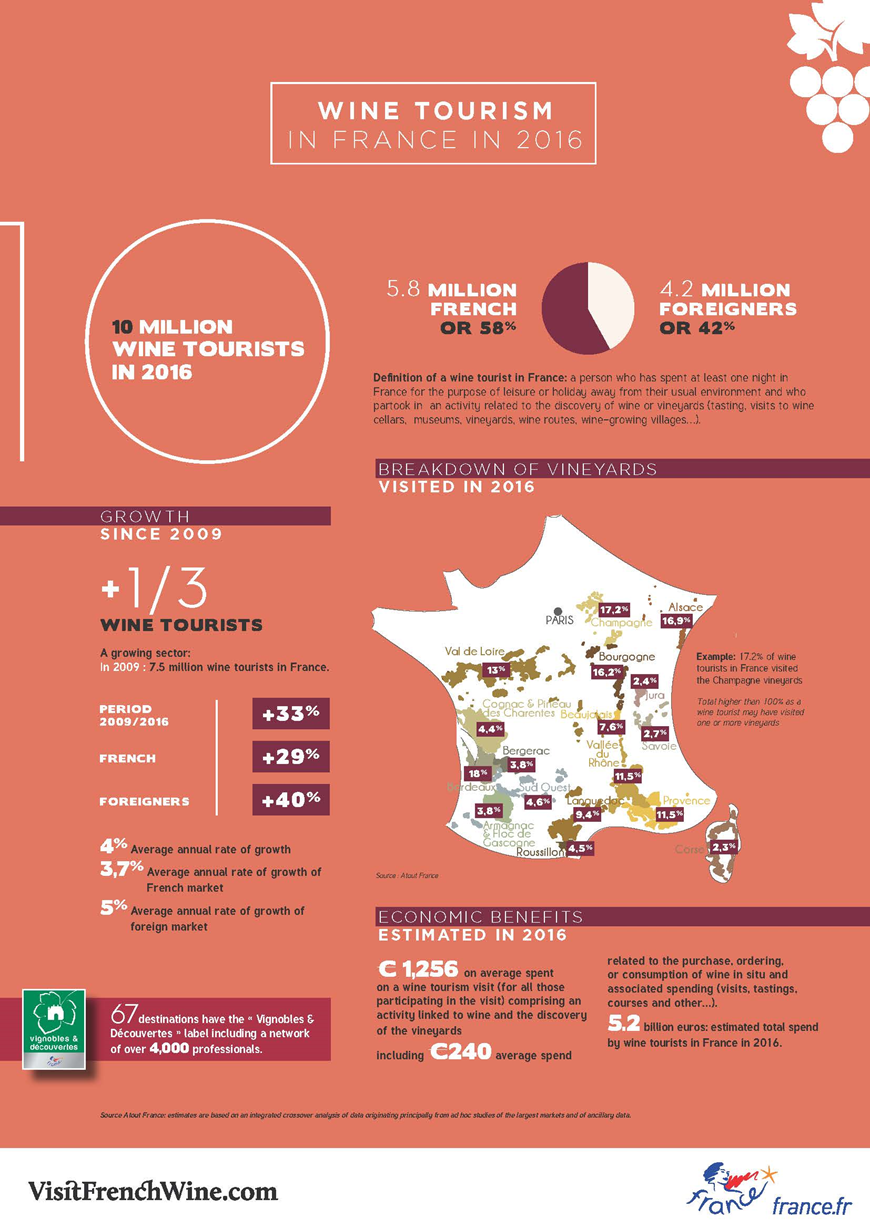

According to Atout France, the France Tourism Development Agency, France had 7.5 million wine tourists in 2009. In 2016, this number increased to 10 million, by more than 30 percent, and wine tourism contributed 5.2 billion euros to the French economy.[iii] In 2009, 58 percent of the wine tourists were from France. Yet in 2016, the number of foreign wine tourists had increased 40 percent since 2009, as contrasted to a 29 percent increase for the French. The Champagne wine region was the second most popular wine region after Bordeaux with 17 percent of the wine tourists. It was considered a major economic generator among the French wine and spirit industry and accounted for 20 percent of French wine sales.[iv] See Exhibit 1 for an overview of wine tourism in France in 2016. French wine tourism experiences included visits to wine cellars, winemaking workshops, overnight Chateaux stays, and walks and hikes through the vineyards.

Source: Atout France[v]

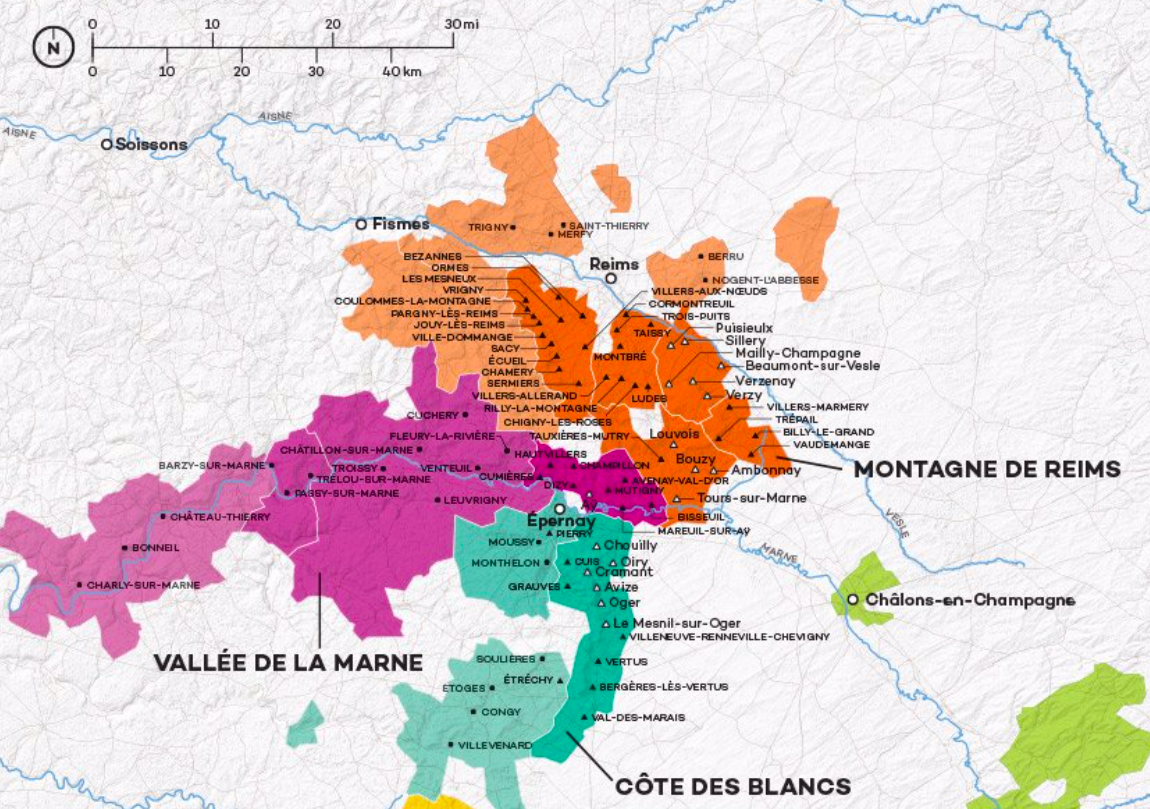

The Champagne wine region, the most northerly wine region in France, was 90 miles east of Paris. There were five major sub-regions of Champagne: Montagne de Reims, Vallée de la Marne, Côte de Blancs, Côte de Sézanne, and Côte des Bars, as shown in Exhibit 2. Statistics from Comité Interprofessionnel du vin de Champagne (CIVC) showed that there were approximately 40,000 hectares (99,000 acres) of vineyards planted throughout Champagne, which accounted for four percent of France’s total vineyard area and 0.5 percent of world vineyard acreage.[vi] The Champagne region was most notably known for its production of sparkling white wine.

Source: Wine Folly[vii]

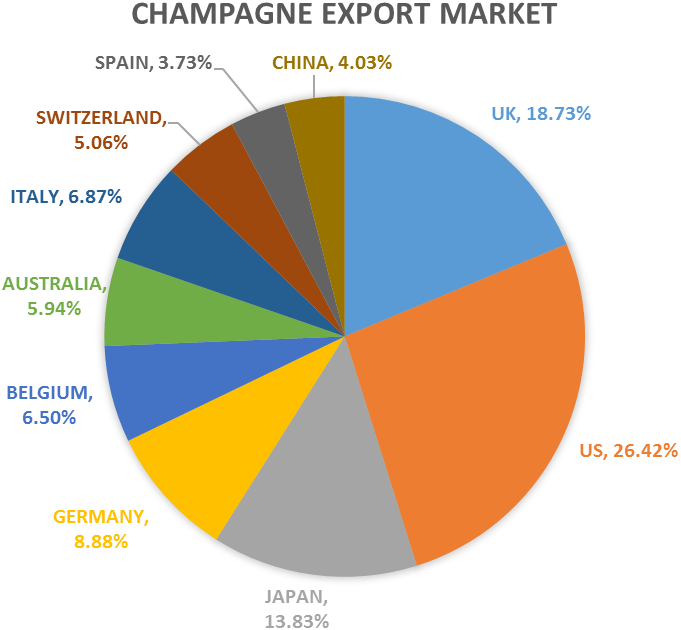

Many champagne houses were founded after the French Revolution in the mid-1800s, and champagne had enjoyed its growing international reputation since then.[viii] While the region suffered significant damage from the Second World War, the 1970s and 1980s saw the Champagne region recover and experienced an increase in demand for its wines. In the late 1990s, the global market for French champagne started increasing, where there were approximately 15,800 winegrowers in the Champagne region and 320 houses of champagne.[ix] Total production reached more than 300 million bottles with 72 percent from champagne houses and 28 percent from the winegrowers and cooperatives. Champagne was recognized as a significant player in the French wine and spirits sector in 2017 with half of the champagne production slated for export, where the top three major export markets were the U.S., U.K., and Japan. See Exhibit 3 for a more complete view of the export market.

Source: CIVC[x]

Montagne de Reims, the location of PdM, was best known viticulturally among all the sub-regions in Champagne with more than 40 villages. The region was also a draw for tourism as it was recognized for its UNESCO World Heritage Sites: Cathedral of Notre-Dame, Former Abbey of Saint-Rémi, and the Palace of Tau. The region of Champagne was also recognized for its UNESCO World Heritage Sites: Avenue de Champagne in Épernay, the historic vineyards of Hautvillers, and the Saint-Nicaise Hill in Reims.[xi]

Champagne as a wine brand

Champagne was considered one of the most well-promoted wine brands in the world. The average price of a champagne grape vineyard was worth at least EUR 1.5 million per hectare, which ranked as the highest valued vinicultural land in the world. Compared to Bordeaux, it valued 60 times higher than the average Bordeaux vineyard. In the past 25 years champagne vineyard prices had increased more than five times, while grape prices had increased only 60 percent in the past 15 years.[xii]

Champagne had to be a sparkling wine; however, not all sparkling wine could be called champagne. Champagne was made from Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, and Pinot Meunier grapes that had been strictly grown from the Champagne region. The making of champagne wine was a continuous process involving varied lengths of time spent in the bottle maturing. Non-vintage champagne spent less time maturing than vintage champagne, and while minimum aging periods were required by law, most big champagne houses kept champagne wine cellared much longer.[xiii]

BACKGROUND OF THE COMPANY

Nathalie Spielmann was an Associate Professor of Marketing at NEOMA Business School, Reims, France. Nathalie was regularly invited to attend and present at conferences because of her marketing expertise. She also worked with the city of Reims and other government agencies developing strategic marketing ideas. Fabrice Parisot, Nathalie’s spouse, was the owner of Les Caves du Forum in downtown Reims. Les Caves du Forum was a cave wine store offering a variety of wines from most of the French wine producing regions. Through Nathalie’s travels to academic and professional conferences, she and Fabrice explored different wine regions together. Nathalie recounted:

We noticed there were always places that we could taste wines representing the region in our travels. However, in Champagne, unless you went to the big houses or made a private appointment with a winemaker in advance, there was no real place for you to taste a glass of champagne. Alternatively, you could visit restaurants or bars, but they were all located in Reims (downtown), and it was not where the product (the champagne) was made. There was a local winemakers’ association that needed help with its promotions. There were about 70 winemakers, who were looking for opportunities to help promote their wines. Looking around and considering all these facts, we decided to come up with a new business plan.[xiv]

Nathalie and Fabrice lived in Rilly-la-Montagne, 12 kilometers (7.5 miles) southeast from the city of Reims. Rilly-la-Montagne was also 15 kilometers (9.3 miles) from Épernay, the capital of Champagne, as shown in Exhibit 2. The village was easily accessible with 22 daily stops from Paris and other cities using the national train system. The village of Rilly-la-Montagne was a scenic place with its 12th century history. After seeking advice and counsel from friends and family, Nathalie and Fabrice decided to move forward on the idea of “opening the only champagne bar and shop in the village.” In early 2017, they purchased a commercial space across the street from the 12th century church on the main road in Rilly-la-Montagne. Nathalie reflected:

One day driving into town, we saw an empty commercial building that stood across the street from the 12th century church. We knew that the land in Champagne was costly; a hectare of vines (2.471 acres) retailed from EUR 1.3 to 1.5 million. Even if we decided one day that we didn’t want to do this anymore, the property would be a great investment.

In April 2017, after proposing the project to winemakers in the village of Rilly-la-Montagne and other nearby villages, Prise de Mousse Bar & Vente de Champagnes opened to the public. It was the only champagne bar and shop in the Montagne de Reims, where it could be characterized as boutique-style, clean, open, airy, and contemporary.

Nathalie came up with their firm’s name, Prise de Mousse, because she liked that it referenced an important stage of the champagne process. “Prise de mousse” was the French term describing that stage of making sparkling wines when the wine becomes effervescent. Nathalie would share when asked about the name:

Literally translated, it meant “taking on bubbles.” Next, the name was in French (we were in France) and also research showed that French brand names were perceived as more hedonic. This was an important facet when one has a champagne bar—we wanted people to have fun. Finally, even people who didn’t speak French could say Prise de Mousse quite easily.

There were two membership options available to winemakers or champagne houses to have their wines featured with PdM. The first membership option enabled their wines to be placed on the wine by the glass list in the bar; this required a monthly fee of EUR 110 plus the value-added tax (VAT), totaling EUR 132.[xv] Typically, four to five different champagnes were featured each week. See Exhibit 4 for an example of its wine by the glass list and pricing. The second membership option enabled PdM to sell the wines for the winemakers and the champagne houses. These wine sales to the customers included an 18 percent markup plus the VAT charge. Prise de Mousse would remit payment of these wine sales from the two membership options to the winemakers and champagne houses quarterly. Prise de Mousse offered other products and services, which included cheese and/or cold cuts plates, merchandise, picnics and wine tasting in the vineyards, visits to winemakers, and other private events. Prise de Mousse marketed and offered champagnes from over 20 villages, although 50 percent of the champagnes were from the village of Rilly-la-Montagne.

|

|

|

|

Wines of the week

(4–6 champagnes & 1 still wine made

in the Champagne region)

|

Price

EUR 6.00–13.50 per glass (10cl per flute)

|

|

Flight of 3 champagnes

|

EUR 20.00 (6cl per flute)

|

|

Flight of 4 champagnes

|

EUR 35.00 (8cl per flute)

|

|

Flight of 6 champagnes |

EUR 40.00 (6cl per flute) |

Source: Prise de Mousse

Prise de Mousse sent its staff, at least once a year, to the member winemakers and champagne houses to taste its wines and get to know them. This was PdM’s way to maintain and strengthen its relationships. While memberships were steady between 20 and 22 winemakers and champagne houses, PdM had lost six and gained one of its producers since opening. Reasons for leaving were varied; some felt sales were not sufficient to sustain the PdM membership or they didn’t have the financial means to stay. Nathalie reflected,

We also realized that having more than 20 partners might not be ideal. We were currently at 22 and thought that if we got closer to 15–18, we would be able to give the partners more visibility. As our business was growing, we could absorb the loss of those membership fees.

Nathalie and Fabrice used a variety of marketing strategies to attract customers to PdM. They worked closely with the local tourism office and with the bed-and-breakfast businesses on the mountain and in the city of Reims. They also engaged in word-of-mouth advertising and social networking websites, such as Facebook, Instagram, and Pinterest. Nathalie and Fabrice offered their tourism and marketing materials in French and English, which was unusual for businesses in Reims. This was their way of letting their Anglophone or English-speaking customers know that they were English friendly. Prise de Mousse had a web presence at https://www.prisedemousse.com/, and its champagnes were shipped within France and to Europe, U.S., and Asia. However, PdM did not conduct e-commerce wine sales.

Prise de Mousse was open Mondays to Fridays from 10:30 am to 2:30 pm and 5:00 pm to 9:00 pm, and while most businesses in town were closed on weekends, PdM was open from 10:30 am to 9:00 pm, regardless of bank holidays. The business was closed on Tuesday and Wednesday afternoons during the winter season. Customers of PdM were a mix of 35 percent domestic visitors (of which locals comprised 15 percent) and 65 percent international visitors, who were primarily from the U.S., U.K., and Australia.

Nathalie and Fabrice both spent about five hours a week taking care of the PdM administrative and management responsibilities. Nathalie was in charge of the accounting, human resources (HR), staffing, marketing, and the image of PdM, while Fabrice managed the stocks, petty cash, inventory, and selection of champagnes. Nathalie brought to PdM her managerial skills as a marketer, and Fabrice brought his wine and wine business acumen as well as his store management expertise.

The firm had three employees on average to assist in the day-to-day activities, which included the preparation of all the food and snacks on the menus. However, the employees were never quite enough to cover all the shifts. In the first year of operation, PdM had nine different employees.

LABOR MARKET—FRANCE AND THE HOSPITALITY INDUSTRY

The labor shortage in France and their local area made it a challenge for Nathalie and Fabrice to find and keep loyal, responsible, and involved talent for PdM. An added challenge was finding bilingual hospitality professionals, whom Nathalie and Fabrice felt were essential to their business when catering to non-French tourists. According to the statistics from the National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies (INSEE), the average unemployment rate in France from 1996 to 2018 was 9.27 percent, and the most recent unemployment rate was 9.1 percent.[xvi]

There were two main types of employment contracts in France: Contrat à Durée Indéterminée (CDI), an open-ended contract, and Contrat à Durée Déterminée (CDD), a fixed-term contract. For a three–12-month fixed-term contract, the employer had to pay an additional EUR 74–EUR 300 depending on the base salary. For an open-ended or indefinite-term employment contract, which included contracts of or exceeding one year, the employer had to pay an extra 55 percent of the employee’s monthly salary, capped at two and a half times the minimum wage. For example, if the base monthly salary was EUR 2,000, the employer had to pay the employee EUR 3,100 in total. The protective labor social system in France also made it difficult to remove an employee who had a permanent contract agreement. For example, if PdM hired someone on a short-term contract, but chose not to continue their employment because they were not working out, PdM would have to pay that person a severance.

Prise de Mousse’s employee salaries were on par (if not higher) for those in the hospitality industry. Additionally, France was experiencing an increase in labor costs, which had reached an all-time high of 108 index points for the past decade.[xvii] The French labor law also regulated that employees were entitled to a minimum of five weeks paid holiday or vacation per year, which was in addition to paid public holidays. It was often the case that many European businesses that did not have sufficient staff to stagger vacations would close its business for a period of time, and thus all employees went on paid holiday at the same time. Prise de Mousse employees received two consecutive days off per week, which was rare in the hospitality industry, but PdM continued to have a high turnover of employees. In 2010, 73 percent of the total turnover in the French hospitality industry was in the food and beverage sector. The bar business was considered the second largest number of all French hospitality businesses with only eight percent turnover and nine percent of the sector employment.[xviii] While there were a large number of bar businesses in France, the village of Rilly-la-Montagne had only one champagne bar and shop—PdM.

LOOKING BACK AND AHEAD

The mission of PdM was to “shepherd your discovery of the Mountain of Reims and its terroir and to enable the best possible champagne experience.”[xix] Nathalie and Fabrice were proud of what they had achieved in their first year of operation. Since opening, PdM was receiving more visitors and sales were steadily increasing. Their hard work was paying off; PdM was making money. See Exhibit 5 for PdM’s monthly sales and growth rate. Prior to PdM operations, the French producers and growers had not really worked well together. Now Nathalie and Fabrice were seeing the beginnings of a solid and long-term relationship with the producers and growers and the growing promotion of champagnes and the Champagne region. Nathalie and Fabrice’s business strategy with PdM included gaining the trust of winemakers and champagne houses to showcase their wines. Membership sales were steadily increasing; 2018 membership sales numbers were on target to exceed 2017 numbers. See Exhibit 6 for membership sales.

|

Source: Prise de Mousse

|

April 2017 through March 2018

|

April 2018 through Oct 2018

|

|

EUR 36,960

|

EUR 24,250

|

After looking at 2018 year-end financials, Nathalie and Fabrice were hopeful for their young business going forward. See Exhibit 7 for the income statement and Exhibit 8 for the balance sheet. They and PdM had received a number of compliments from locals and visitors, alike. The business received positive reviews in the local French press, including Champagne Viticole, Le Point, Terre & Vines, and L’union. They were getting recognized. Nathalie and Fabrice won the Young Talents of Tourism competition in 2018, which promotes “creative professionals who display remarkable know-how.”[xx]

|

|

EUR

|

|

Sales of goods purchased for resale (Domestic)

|

173,461

|

|

Sales of goods purchased for resale (Export)

|

854

|

|

Sales for services

|

37,580

|

|

Total Revenue

|

211,895

|

|

|

|

|

Cost of Goods Sold

|

123,409

|

|

|

|

|

Gross Profit

|

88,486

|

|

|

|

|

Operating Expense

|

75,586

|

|

|

|

|

Operating Profit

|

12,900

|

|

Other income/expense

|

2

|

|

|

|

|

Earnings Before Interest & Tax (EBIT)

|

12,902

|

|

Interest expense

|

653

|

|

Income tax expense

|

1,165

|

|

|

|

|

Net Income

|

11,084

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fixed Assets

|

EUR

|

|

Concessions, patents, licenses, trademarks, & similar rights

|

774

|

|

Industrial fixtures, fittings, plant machinery, & equipment

|

4,139

|

|

Other tangible fixed assets

|

35,403

|

|

Other shares in subsidiaries and associated companies

|

598

|

|

Other financial fixed assets

|

1,296

|

|

Total Fixed Assets

|

42,210

|

|

Current Assets

|

|

|

Inventories of goods purchased for resale

|

14,991

|

|

Advances and payments

|

183

|

|

State taxes on profits

|

1,017

|

|

State turnover taxes

|

795

|

|

Cash

|

20,642

|

|

Prepaid expenses

|

1,008

|

|

Others

|

915

|

|

Total current assets

|

39,551

|

|

Total Assets

|

81,761

|

|

|

|

|

Current Liability

|

|

|

Received advances and prepayments

|

3,306

|

|

Trade accounts payable

|

12,424

|

|

Paid vacation

|

478

|

|

Social organizations

|

1,975

|

|

Total Current Liability

|

18,183

|

|

Long-Term Liability

|

|

|

State turnover taxes

|

3,674

|

|

Deferred income taxes

|

2,063

|

|

Other debenture loans

|

43,152

|

|

Associate loans

|

1,105

|

|

Total Long-Term Liability

|

49,994

|

|

Total Liability

|

68,177

|

|

Equity

|

|

|

Capital stocks including paid capital

|

2,500

|

|

Result for the year (profit)

|

11,084

|

|

Net Equity

|

13,584

|

|

Total Liability & Equity

|

81,761

|

|

|

|

The personalized aspect of the business was important for Nathalie and Fabrice. They had wanted and hoped that when customers came to PdM, the patrons would feel like they were in someone’s home. The result of their visit to PdM was to be their discovery of champagne and the champagnes surrounding the hills of Reims. If the customers left having had that “Oh, wow!”, “I never knew that.”, or “That’s so cool!” experience, then Nathalie and Fabrice felt like they had succeeded.

Nathalie reflected on what she saw as the differences between champagne tourism and other French wine tourism such as Burgundy and Bordeaux:

Champagne had been fairly closed off in terms of wine tourism in the past. This was probably due to the fact that the champagne industry was doing so well domestically—producers didn’t have to sell their champagne, it sold itself. Not to mention that champagne producers were very well paid per kg of grapes (around EUR 6). As well, people often assimilated champagne with Paris, so they never really came to Champagne (even though it’s only a 45-minute train ride away). In contrast, Bordeaux and Burgundy had always had a sales approach—the two regions were distinct from Paris, had a history of sales (especially Bordeaux with the Primeur) and because the price of grapes was much lower, I think many firms had to seek out ways to diversify. Now, the recent figures from the CIVC showed that the domestic market was at an all-time low for champagne. As well, we recently received UNESCO recognition in Champagne, which had boosted oenotourism (wine tourism) and interest for the region. Consequently, Champagne has had to try to focus and invest in tourism.

The Bordeaux region welcomed the most wine tourists in France, followed by Champagne. Prise de Mousse represented Champagne, however, as its sole champagne bar and retail business in 2019. Prise de Mousse’s unrivaled singularity plus its success and growth suggested to Nathalie and Fabrice that they could be on to something big. Considering their prior work commitments, financial obligations, and labor shortage challenges, the co-owners weighed their options. Where should Nathalie and Fabrice go from here? A question remained: to franchise or not to franchise?

[i] About us. (2018, December 18). Retrieved from http://atout-france.fr/content/about-us

[ii] Hackett, N.C. (1996). Surprise Success: Wine, Tourists, and the Woes of Free Trade. Burnaby: Centre for Tourism Policy and Research (Simon Fraser University).

[iii] About us. (2018, December 18). Retrieved from http://atout-france.fr/content/about-us

[iv] Why is champagne so cheap? (2019, November 26). Retrieved from https://www.tysonstelzer.com/why-is-champagne-so-cheap/

[v] About us. (2018, December 18). Retrieved from http://atout-france.fr/content/about-us

[vi] The Champagne industry. (n.d.). Retrieved November 26, 2019, from https://www.champagne.fr/en/champagne-economy/champagne-industry

[vii] Champagne Map (Infographic). (2015, October 24). Retrieved December 10, 2018, from https://winefolly.com/review/champagne-map-infographic/

[viii] Champagne House, “an agricultural and/or industrial and commercial business (but not exclusively agricultural) that commands the human and natural resources required to produce Grande Marque Champagne for distribution worldwide.” (n.d.). Retrieved Dec 10, 2018, from http://maisons-champagne.com/en/houses/the-champagne-houses/article/defi...

[ix] CIVC. Retrieved Dec 10, 2018, from https://www.champagne.fr/assets/files/economie/filiere-champagne/plaquet...ère_uk_2018.pdf

[x] The Champagne industry. (n.d.). Retrieved November 26, 2019, from https://www.champagne.fr/en/champagne-economy/champagne-industry

[xi] UNESCO, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, is a specialized agency of the United Nations based in Paris, France.

[xii] Why is champagne so cheap? (2019, November 26). Retrieved from https://www.tysonstelzer.com/why-is-champagne-so-cheap/

[xiii] Ibid

[xiv] All subsequent quotations with the owner are from interviews with the case writer.

[xv] VAT refers to value-added tax, the sales tax on goods and services in France, 20 percent standard rate.

[xvi] (n.d.). Retrieved December 10, 2018, from https://tradingeconomics.com/france/indicators

[xvii] Ibid

[xviii] EY Publication. (September, 2013). The Hospitality Sector in Europe. Retrieved Dec 10, 2018, from https://www.ey.com/Publication/vwLUAssets/The_Hospitality_Sector_in_Europe/$FILE/EY_The_Hospitality_Sector_in_Europe.pdf

[xix] Philosophy/ie. (n.d.). Retrieved December 10, 2018, from https://www.prisedemousse.com/story

[xx] Le palmarès 2018 est .... (n.d.). Retrieved November 6, 2019, from http://www.lesjeunestalentsdutourisme.com/?p=1292